It doesn’t take much conversation to discover that Beth Ireland, a Boston-area professional woodworker and educator, has a “fire in the belly.” It’s all about hands-on learning, kids and bringing the two together any way she can.

“There’s a disempowerment happening in our country, and it’s getting worse and worse all the time. It’s like people under the age of 40 don’t know how to make things anymore, because they never learned how in school. That kind of thing is second nature with me. I don’t think it’s getting better soon enough, and it needs to start with kids,” Ireland says.

That fire in the belly, though, was only kindled relatively recently. A self-proclaimed workaholic, Beth opened Beth Ireland Woodworking in 1983 and focused 60 to 70 hours per week for more than 20 years building commissioned furniture, chairs and tables. She’s also routinely taught at various woodworking schools around the country, but mostly, her focus was on running her business. It was head-down and nose-to-the-grindstone time.

Then, almost by “happenstance” as she says, things started to change. In 2008 Beth decided to take a couple years off and do graduate work in sculpture at Massachusetts College of Art and Design. Around that time she met Jennifer Moller, a fellow educator, professional photographer and digital media maker (whose photos are featured here). The two collaborated on several art shows and began to notice an unsettling trend among many of Beth’s fellow graduate students.

“I found myself teaching many of my classmates how to use basic woodworking and shop tools … plus how to make things with their hands. Here they were studying graduate-level art, and they couldn’t use tools. It was crazy, really!” Ireland recalls.

When Beth was nearly finished with grad school, she and Jen set out to do something about that void in hands-on education. “Graduate school was a chance for us to stop and ask, ‘What is the meaning of my work? What’s happening to my culture?'” And part of those answers came by way of a 25,000-mile, cross-country woodworking immersion experience the two began to plan, called “Turning Around America.” It would be a grassroots enterprise, where Beth would travel to cities around America to “plant the seeds of woodworking” through basic skills education. Jen would document her progress on a website and blog she created.

“Our philosophy about the trip was pretty simple: we intended it to be a relational, aesthetic art project in which I would help empower people through the simple act of making something out of wood. It would be a one-time thing, and I planned to spend a year doing it,” she says.

Ireland and Moller retrofitted a 2005 Chevy cargo van with all the essentials Beth would need to live and teach from her vehicle. They called it the Mobile Workshop. In the back compartment, she carried two mini-lathes, a bandsaw, grinder, 26 clamps and bins upon bins of other hand tools. In the front living space, there’s a double bed, chemical toilet, sink and fold-down desk. A solar panel would help power her laptop, and an electric generator would feed the woodworking tools.

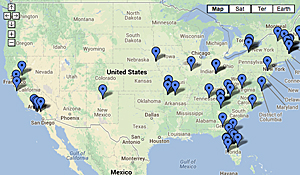

The initial itinerary was admittedly loose. Beth would set out from Boston in October 2010. She would stop and do woodturning demos for newbie woodworkers, hosted by ten woodworking guilds spread out from New York to California. Participants would have a chance to make whistles, tool handles and pens either on the lathe under her tutelage, or for the l and coloring a whistle or pen cylinder she prepared for them.

As the trip got underway, news of her planned visits began to spread to other woodturning clubs and area teachers, who called her to set up more visits in stopover cities or to add more cities to her logbook. When Turning Around America concluded eight months later on June 1, Ireland had helped almost 3,000 people create their own handmade object. She says she lectured to far more people than that.

“The turnout, and the whole experience really, was tremendous for me,” Beth says. It was also life-changing. Not even three months after returning home, she and Jen got a call from a Guatemalan who had attended one of her Turning Around America events. He wanted the two to come to his remote village and teach basic woodworking, woodturning and sharpening skills. Ireland and Moller spent three weeks there in February 2012. Among other successes, the two helped villagers turn a cast-off automotive differential into a working wood lathe.

“Those villagers we taught began to teach others how to turn wood, too. It showed us that there’s something to this form of mobile education we’re doing … it can empower people to learn, and then empower others.”

But while the need was great in Guatemala, Beth’s most recent mobile education project “Turning Around Boston” reflects her belief that there’s much to be done right here at home. It concluded just last week. This time, she and Jen partnered with the Eliot School of Fine and Applied Arts, a Boston-area school that teaches people of all ages various crafts, including woodworking. In a similar vein to Turning Around America, the Boston intensive was straightforward: spend the month of October driving the Mobile Workshop around to Boston public schools and teaching as many kids as possible how to make something with their hands. The Eliot School provided Beth both volunteer teachers and grant money raised through a Kickstarter project. Jen and Beth shared the teaching responsibilities.

Ireland says Boston’s broad ethnicity and socioeconomic challenges put her and Jen in touch with kids from all walks of life: some from affluent communities with well-funded schools, and others who are much less fortunate. Regardless, Ireland says teachers are continuing to contact them now, “and often they’re saying nearly the same thing: that they had never seen their school kids so focused as when we were making whistles and pens with them.”

While Beth admits that she didn’t count the final number of students taught or schools visited last month, only about 30 of the 1,050 turning blanks she had prepared initially are leftover now. The rest have gone home with the children who made them into their own finished works of art.

Why the heightened interest among kids? Beth is certain that part of the excitement stems from what mainstream education isn’t doing, or isn’t doing often enough: providing hands-on ways for kids to learn actively instead of passively. Kids spend too much time sitting in chairs, she feels, and don’t have opportunities to do things like saw, file, drill, turn on a lathe, paint or mold clay, all vital opportunities for hands-on learning.

“When I was a kid, I was dyslexic and failed many of my tests. I needed education to be in a physical, hands-on world, not in the sort of lineal, cognitive mode that kids are learning from today. They spend so much time sitting and listening, then repeating what they learn. We need to touch things sometimes and make them physical to learn about them, too. I probably wouldn’t have failed geometry if I could have understood math in the context of woodworking, like I do now.”

And, of course, part of the success of both the national and Boston-area “Turning” events stems from the fact that making something is just plain fun, no matter the age of the learner. We woodworkers know that full well.

With Turning Around Boston now behind them, the next phase of Ireland and Moller’s mobile education efforts will involve a rolling studio for Jen, which is under construction now. It’s a 14-foot flatbed trailer the two are converting into a bookmaking, digital media and printmaking studio. They’re calling it the Sanctuary and, like Beth’s Chevy mobile woodworking shop, the Sanctuary will be largely self-sustaining. Beth says it is equipped with a 40 x 78-in. work surface, bed, composting toilet, a solar hot water heater and solar panels for generating electricity. Next July, Ireland and Moller will take both mobile workshops to Shepherdstown, West Virginia, where they will lead hands-on learning projects for the whole town.

As Beth and Jen look further into the future, there are broader ambitions for expanding their education on wheels. “Someday we’d like to create a ‘Craft Caravan’ of four or five of these trailers or vans so we could bring other self-sustaining artists with us to teach a variety of different art forms,” Beth speculates. Whether it’s woodworking, printmaking, pottery or otherwise, “what’s important is to get the creative juices flowing and convince people that they really can do this … they can make things with their hands!”

Beth and Jen also hope to develop curriculum that will be rooted in hands-on education for young people going into teaching fields.

It’s going to take substantial funding to continue this sort of mobile outreach, Beth says, and time commitment. Aside from Mobile Workshop and Sanctuary activities, Ireland and Moller are continuing their “day jobs” as working artists. So, the long-term success of their mobile teaching efforts is uncertain. In the spirit of the Guatemalan village, Beth insists that it’s going to take many, not just two individuals, for this sort of hands-on learning to continue. “Volunteers are so important, and so is their ability to nurture the community of fellow volunteers.”

But, good things happen when learning becomes active, and it’s proven itself to Ireland both abroad and at home in just a few years “on the road.” The “doing” is the thing, whether it’s teaching a second grader to turn a whistle blank or a grad student to run a table saw.

“Once you touch a tool and a piece of wood, the possibilities are endless … The importance of getting tools in your hands leads to creative problem-solving. I really believe the answers to so much learning are right here in our hands. We just need to use them.”