Last week’s editorial was about nuts: tree nuts, in particular, and wood that comes from those trees.

We heard about readers’ favorite nut woods for woodworking. – Editor

“My favorite ‘nutty’ woods are walnut and cherry, with red oak used more because it’s cheaper!” – Dale Smith

“I have only worked with beech. I like its toughness and strength for projects that take a beating. On one occasion, I used it to build a flag case for the American flag my son received when he became an Eagle Scout. When I sanded it down to 220-grit, I noticed a faint wavy pattern so I took it down to 320, then 400 and finally 600-grit. A beautiful ray pattern appeared. When I hit it with shellac followed by woodworkers wipe-on formula, I discovered what other woodworkers were talking about when they wrote about chatoyance.” – Lee Ohmart

And that the Oklahoma area is seeing a bumper crop of acorns this year – so much so that the squirrels can’t keep up with their “planting season.” – Editor

“It has been wet this year in Oklahoma. The squirrels, deer, raccoons, armadillos, packrats, and pocket gophers are no match for what is coming off the trees. Strangely enough, the pecans and black walnuts do not seem to have the same proliferation.” – Riley G.

We also heard about chestnuts: a plea for suggestions on what to do with Japanese chestnuts, and a note about where remnants of the American chestnut may still linger. – Editor

“Just wanted to point out that while the American chestnut is endangered, there are still a fair number of Japanese chestnut trees in the country, which are resistant to the blight. My tree (three four-foot trunks) bombards my yard with fruit quite thoroughly each fall, along with an occasional branch; hardhats really are not a bad idea during those weeks. Alas, the nuts are inedible, to the great frustration of both me and the neighborhood squirrels, and the self-pruned branches aren’t enough solid wood that I’ve been able to do anything with them yet. If anyone can suggest something to do with the nuts, other than stringing them into wreaths, I’d welcome suggestions. It seem a pity to waste all that yearly effort.” – Joseph Kesselman

“I assume you understand American chestnuts still sprout from the roots of the old trees and grow up to a few inches in diameter in the upper elevations before the insects kill these sprouts. The wood is a much lighter shade when fresh cut than the seasoned wood most people are familiar with. American chestnut was a strong, easy to work, and more lightweight wood that was used in framing, wall panels and almost everything else. If you would like to see some of the newer cuttings, you could contact the forestry instructors at Glenville State College in Glenville, West Virginia, as they had same they provided students when I studied there, and might share one with you. If you wish to find some, these will be in the upper elevations where the insects were not as abundant, but the warmer climate may have had an effect on this as well.” – D. R. Bickel

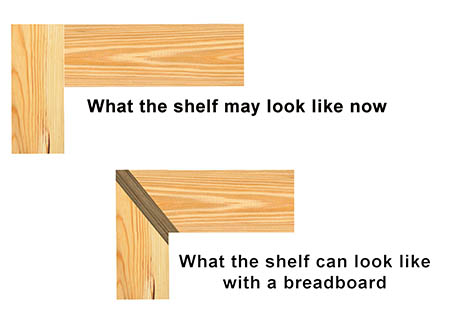

We also heard from a reader who had his own suggestion for a response to last issue’s question on the Best Way to Fix a Corner Shelf. – Editor

OK, folks, here’s a fix that I’ve used before with great success. It all comes down to tables. Now don’t scratch your heads too much, and think of those breadboard ends. There is nothing in the rule book that says you cannot apply the breadboard concept to corner shelves. What I have done in the past is to create a ‘double’ breadboard where the shelf parts on the left and the ones on the right feed into the breadboard. While not looking like the original corner shelves, this method will give you a unique decorative accent to each shelf, especially if you use contrasting woods.” – Phil Rasmussen

Phil also shared a few additional uses for last issue’s Doweling Jig that Doubles as a Drill Press. – Editor

“There are many uses for a self-centering doweling jig as shown in the recent eZine. Here are three such uses: 1.Place it over the edge of a board and tighten it until it just slides along the board. Put in the ¼-inch dowel guide and pencil and, voila, you have a centering jig as you slide the jig along the board. 2. Similar to the article and above, you can replace the drill bit with a up-spiral router bit to cut those mortises. (Be sure your router bit is sharp). 3. With a Forstner or brad point bit, find the center of a small dowel when you insert the end of a ‘smallish’ dowel into the drill guides of the jig. You may have to remove a guide.” – Phil Rasmussen