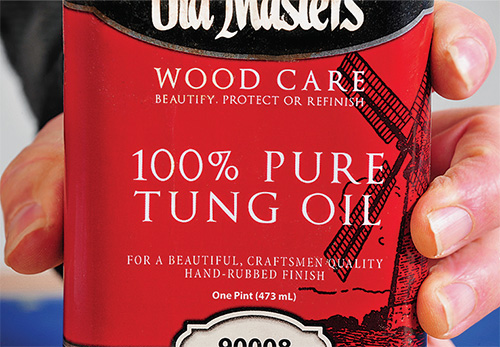

Oil finishes are an ideal match for wood. They are incredibly easy to apply, very beautiful, and some of them are extremely eco-friendly. As finishes, they divide into two large categories — pure oil and oil/resin varnishes. We’ll start with pure oil.

Drying vs. Non-drying

There are two types of oils — drying oils and non-drying oils. In my mind, drying oils are the only valid finishing oils. They start out as liquids, but they cure to a solid film. To me, that’s the definition of a finish.

Typically, nut oils are drying oils, and the most common ones we use are linseed, tung and walnut. These drying oils cure by taking oxygen from the air and crosslinking the oil molecules into much larger molecules. Once the new molecules get big enough, the resulting matrix they form becomes a solid instead of a liquid, forming a film either in the wood or on the wood.

The most common is boiled linseed oil (BLO), which, in spite of its name, is neither boiled nor heated. Instead, it contains metallic drier that speeds up the cure time. A coat of raw linseed oil will take over a week to dry; one of BLO will often dry overnight. Tung oil dries quickly by itself, so it generally does not need driers added to it. Unmodified walnut oil dries even more slowly than raw linseed oil, which is why I avoid it.

Non-drying oils are usually vegetable (peanut, olive, corn, coconut, rapeseed) or mineral oil, which is extracted from petroleum. Orange and lemon oil, typically mineral oil with citrus scent added, are also in this group.

These do not form a film but stay wet indefinitely. They can come off onto whatever comes in contact with the oiled wood, and they will soon wash off with soap and water.

Thus, putting vegetable or mineral oil on wood is not a finish, but a wood treatment, and a temporary one at that.

Important Safety Note!

Drying oils are spontaneously combustible. Take all rags and wipes containing drying oils and lay them out one layer thick until they are dry and crusty, at which point they can be safely added to your household trash.

VOCs vs. Solids

Concerned about VOCs? Those are the finish solvents, restricted by the EPA, that can cause dangerous ozone buildup in the presence of sunlight. Pure oil has none whatsoever, because it has no solvent in it. Thus, it is a 100% solids finish. Solids are whatever stays on the wood, after the solvent, to become the film. Clearly, this is a very eco-friendly finish; it comes from plants and contains no solvents, harmful or otherwise.

Where’s the Film?

In many woods, the first coat of oil penetrates and is almost entirely absorbed by the wood, so it does not look like a film was formed. It’s there, but it is in the wood, not atop it. The oil cures in the outer layers of wood fibers. But even if you add no more than one coat, cured oil will still help the wood shed water, oils, dirt and some, but not all, of the things that stain wood. Add more and you get more protection. Multiple coats can eventually build up a gloss film.

Applying Oil

Do not add solvent to pure oil. It will not, as some believe, increase absorption, and will only reduce the amount of protective film per coat while contributing to environmental problems.

Flood oil onto the wood liberally, keeping it wet for at least 10 minutes. If areas of the wood absorb all the oil in under 10 minutes, add more, keeping the whole surface fully wet. When it stops absorbing oil, wipe all the oil off the surface. You’ll have a uniform, dustfree coat with almost no effort.

Want more build? Do the same thing the next day, and the next, adding one flooded on/wiped off coat per day until you get the look you want. One coat will look woody and natural, while 12 coats (over 12 days) will look like traditional varnish.

To speed the process, or create a slurry to help fill open pores, sand the oil into the wood with fine wet/dry paper.

Oil Varnish

Where oil has only one ingredient, varnish contains resin and solvent. Traditional spar varnish, for instance, contains tung oil, phenolic resin and mineral spirits or naphtha. The most common varnish resins, alkyd and polyurethane, can be made by chemically modifying linseed oil.

In spite of their names, Danish oil and teak oil are not oils, but thin varnishes. Manufacturers call them “oil” because they are designed to be applied just like oil. The truth is that you can apply any oil varnish the same way you apply pure oil: flood it on, wipe it all off, and repeat with one coat per day until you get the build you want.

Forget the Solvent

Whether it’s Danish oil or polyurethane varnish, there’s no need to thin it for this type of application: any solvent only acts as a diluent and does not effect how well the finish penetrates the wood.

With thicker varnish, a nylon pad (such as ScotchBrite®) works best to scrub the varnish on before wiping it off. Of course, should you prefer to spray or brush thick varnish, you’ll likely have to thin it for workability.

Exceptions

There are a few woods over which oils will not cure properly. Notable among them are most Dalbergias (rosewoods) and some aromatic cedars.

Remember how oil and oil varnish cure by using oxygen from the air to crosslink the molecules? Such “problem” woods contain antioxidants that prevent oxygen cure.

The solution? Seal them first with a thin coat of dewaxed shellac, after which you can switch to oil varnish.

But What About Nut Allergies?

Once they cure, drying oils, which are usually nut oils, form a solid, inert matrix that will not come off on your hands or in your mouth. Thus, the odds of a negative reaction should be substantially less than with wet oil.

Anything can happen, but in more than 45 years in this field, I’ve never seen an allergic reaction to a cured film of linseed oil.