Woodworkers have an opportunity to see world-class nineteenth century decor at the newly opened Eustis Estate in Milton, Massachusetts. Owned by the Eustis Family for three generations, it was purchased by Historic New England in 2012. The 1878 mansion has dazzling woodwork: beautifully carved ceiling beams, stairways, elaborate furniture and a variety of wood. There are 14 fireplaces, nine with truly impressive decoration. One of the fireplaces has over 60 carved flowers with individual petals. It is the latest addition to 36 other Historic New England properties. Michaela Neiro, objects conservator, says, “What struck me immediately when I first went to the mansion was the sheer quantity of the wood and that it was in very good condition. I describe it as quality, quantity and diversity.” The Eustis Estate is opulent and Peter Gittleman, visitor experience team leader and a wood refinisher himself, says, “This is amazing woodwork and it is pretty hard to oversell it.”

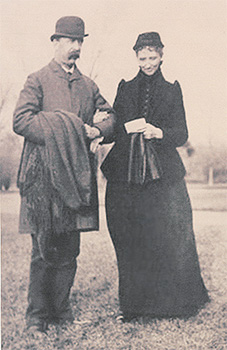

The story of the Eustis Mansion began on November 7, 1876, when Edith Hemenway married W. E. C. Eustis. Peter says, “The Hemenway and Eustis family properties in Milton bordered each other. Edith’s mother, Mary Hemenway, gave the couple approximately 181 acres on the adjoining properties to build their new home.” Historic New England describes the Queen Anne style mansion as “a marvel of the Aesthetic Movement.” Locally prominent architect William Ralph Emerson designed the home. Peter says, “Unfortunately, not many of William Ralph Emerson’s papers survived. There isn’t one great repository of his work and that is regrettable because he was pretty prolific. Today, Emerson isn’t very well-known and just recently two of his fantastic houses in the area have been demolished. We are hoping the Eustis Estate will shed new light on Emerson’s body of work.” (Emerson was the fourth cousin of author Ralph Waldo Emerson.) Regarding the decor, Peter says, “We don’t know if the emphasis on wood was determined by the young couple, Emerson, interior designers or Edith’s mother, Mary Hemenway.”

Detective work has tracked down many of the craftsmen who worked on the mansion. Unfortunately, the woodworker remains a mystery. Evidence points to a Boston carver, possibly a German, named Caspar W. Roeth. Peter says, “There aren’t any maker’s marks visible on the wood, but Roeth was working with Emerson at the time the Eustis mansion was being built.” Roeth’s obituary in the Boston Journal on November 21, 1891, described him as a “well known manufacturer of artistic furniture and a decorator of buildings.”

Peter notes, “The family’s heavily carved wooden furniture was likely purchased on the couple’s Italian honeymoon in 1876. We found the word ‘Firenze’ underneath one of the pieces, so we feel confident that it came from Florence. Some carved panels in the mansion might have been done by Luigi Frullini. He was working on the Chateausur-Mer mansion in Newport, Rhode Island, at the same time the Eustis Mansion was being built. The fireplaces do not have any identification, but there isn’t any evidence they were imported. This is still a new property for us. We have only been in the house for two years, and we hope to learn much more.”

Michaela adds, “The mansion has all types of wood, and the carvings have subtle differences throughout the building. Every time I looked at a section of wood, I found something different. In the dining room, there are birds and grapevines. Some paneling has starbursts, swirls; upstairs, there are faces and cartouches. The carving is very playful. The wood is not constrained by one pattern throughout the house. Many houses often have the same types of wood and motif throughout, but not here. The elaborately carved fireplaces all have different style variations; some of them are subtle.” She suspects “the fireplace in the dining room might be by someone not part of the larger woodwork project. It looks like a different hand.”

Overall, Michaela said, “The wood is in extremely good condition. The family took very good care of it, and it shows. I can imagine them telling the children to be careful playing in the house.”

Liz Peirce, a Mellon Fellow in art conservation who worked on the Eustis restoration, detailed the cleaning process: “We used a mild citrate solution on the woodwork, cleaning with a combination of soft rags, swabs and brushes. We use a 2% citrate solution that has been buffered to approximately pH 8. We use a chemical grade citric acid powder, which is then dissolved in water before adding a base to adjust the pH. In some cases, if the dirt was particularly grimy, a very small amount of benzyl alcohol was added (0.05%) to help cut through grease. When dry, the woodwork was then waxed with either clear paste wax for flat surfaces or a tinted paste wax for highly carved decoration. The clear paste wax dries white, and is difficult to buff out from crevices. Toned waxes are less glaring, should any be left in nooks and crannies. The wax was then buffed with a soft cloth. For heavily handled places, like the stairway railing, the clear paste wax was applied twice to build up a protective layer.”

Peter said, “As we were making the final preparations for opening the museum, we gave our office staff a chance to get involved and had volunteer days. People who work at Historic New England love old houses. They welcomed the opportunity to work on the beautiful wood.” Peter also emphasized that “Any restoration work has to be reversible. Anything added may have to be removed at a later date. The restoration in the house doesn’t look ‘perfect.’ We wanted the house to show age and the wood’s patina.”

The Eustis family sold the museum several rooms of original family furniture. However, the sheer size of the mansion led to a revolutionary idea. Peter said, “We wanted to have a furnished look. Period furniture was obtained through dealers and auction houses specifically for use by visitors doing self-guided tours. Information for each room can be found on tethered computer tablets. The only custom-made furniture is a set of Mission-style side tables that accommodate the tablets; the power cords run inside one of the legs.” This is a museum where people can sit on the chairs!

Historic New England, originally known as the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, was founded in 1910 by William Sumner Appleton. Anyone interested in traditional architecture, carpentry and historic furniture would enjoy visiting their 37 properties. The oldest is the 1664 Jackson House in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and the newest, the 1938 Gropius House in Lincoln, Massachusetts. The Eustis Estate is particularly worth a visit by anyone who loves Victorian woodworking.

For more information, visit the websites www.eustis.estate or www.historicnewengland.org or call the Eustis Estate at 617-994-6600 or Historic New England at 617-227-3956.