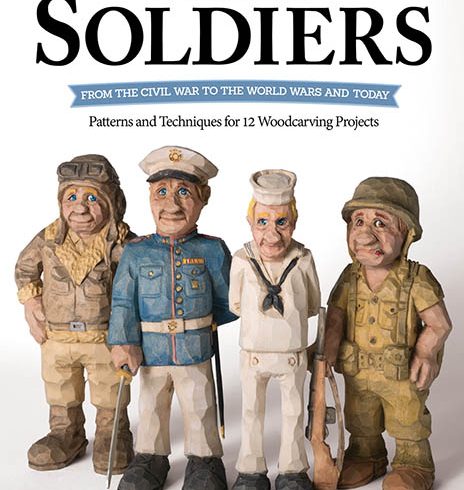

Floyd Rhadigan started woodcarving, introduced to it by a family friend, back in 1970 at the age of 18. Forty-seven years later, he estimates he has made at least 10,000 carvings, and has spent the last 15 years dedicated to carving and teaching. Plus, he’s got a new book out, Caricature Soldiers: From the Civil War to the World Wars and Today.

When Floyd first started woodcarving, palm tools hadn’t been invented yet: all that was available, he said, were the full-size mallet tools used with a wooden mallet. “You had to choke down on them like you would on a baseball bat, and hold on to the metal part to use it safely.”

Then in 1975, Floyd came across a book by Harold Enlow, Carving Figure Caricatures in the Ozark Style. Enlow not only introduced palm-size tools, but Floyd describes him as “the grandfather of caricature carving in the United States.” Upon reading that book, he said, “I was hooked. I knew caricature carving was what I wanted to do.”

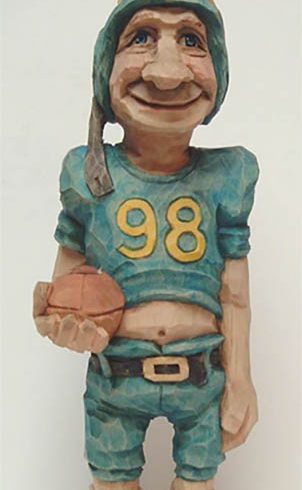

The appeal of caricatures? “I like to see people smile,” Floyd said. “It’s fun. It’s cartooning with wood.” Plus, he added, there are so many different things you can turn into a caricature: people, animals, kitchen utensils … the list goes on. “I have a good imagination. When I was younger, it used to get me into a lot of trouble,” Floyd said, but in the carving world, that imagination is an asset.

Among his carvings are some that are special to him, including “Cool Cat,” which depicts a cat sitting on an amplifier playing a Fender guitar. Floyd did the original for his son. He also greatly enjoyed “Road to Mirth and Happiness,” a carving of a circus wagon filled with dogs dressed as clowns, pulled by a chihuahua harnessed to the wagon.

That’s the piece that won Floyd a Best in Show at the 2005 Caricature Carvers of America competition. This was before Floyd was voted into the group of about 25 active and roughly 15 emeritus members who meet once a year to work on projects together and sometimes collaborate on books. “It’s like belonging to a club where all your heroes are members,” Floyd said.

For the most part, Floyd said, “Woodcarvers share their plans, their materials, their tools.” He travels with and sells rough outs of the carvings he has developed to his students across the country. Generally, he has about 60 different carving options, with about a dozen rough outs of each, in his full-size Ford van – with that, plus tools, “I pack it pretty much to the ceiling,” Floyd said.

The rough outs, a rough shape of a carving to which a student or other woodcarver adds the details, make it easier to teach rather than using a band saw blank that provides just the face and side of the carving, Floyd said. He has a friend in Missouri who creates his rough outs on a duplicating machine, which can produce 12 or 24 pieces at a time. The friend has 159 of Floyd’s masters in stock, and Floyd rotates which ones are available, since “I can’t carry everything.”

His full-time woodcarving and teaching come after about a 30-year career as a sign painter. After leaving the military, Floyd became a sign painter, following in his father’s career footsteps, because that’s what he knew how to do. He painted trucks and boats, added pinstriping to motorcycles, and more, before “I got to where I didn’t want to be climbing up on a ladder and digging post holes.”

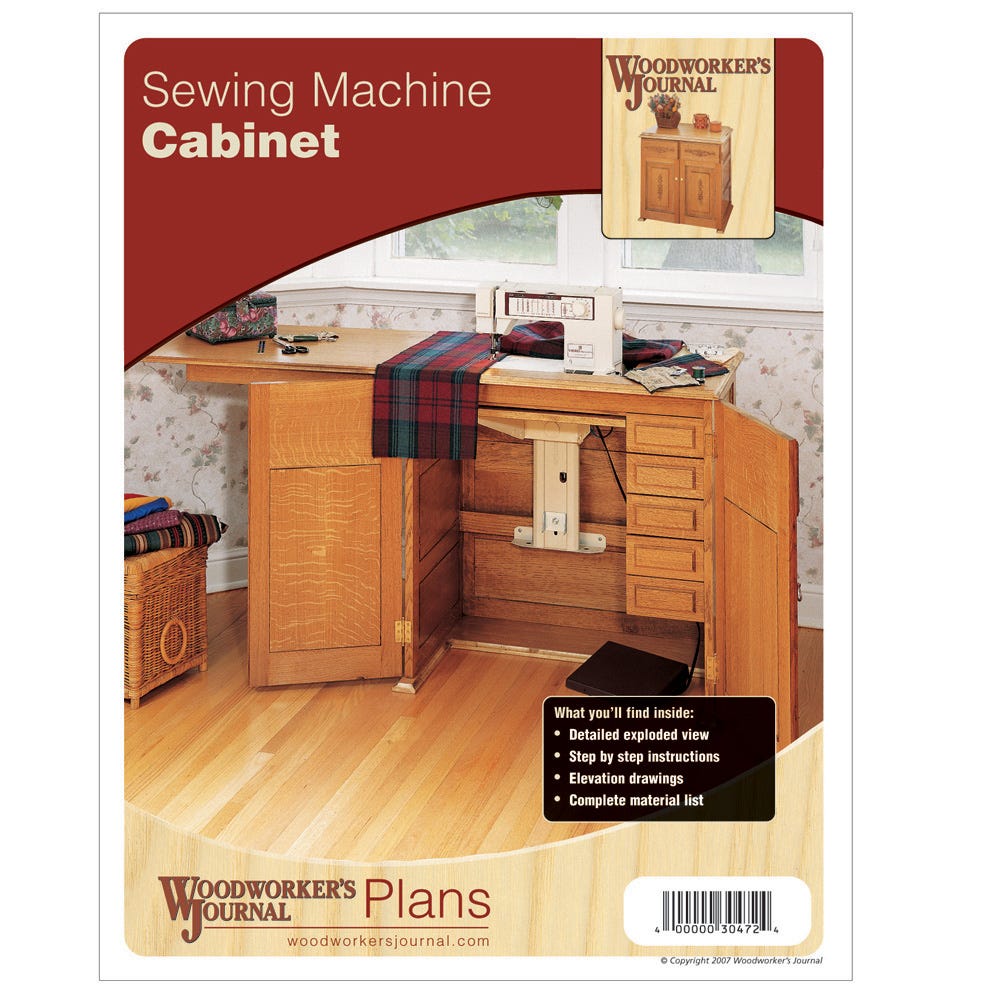

Floyd also used to do a lot of furniture making, including dining room sets and china cabinets. Now, “I’m too busy doing just carving, but I love any kind of woodworking. It gives you great satisfaction to take a board and make something out of it.”

For the most part, he uses basswood, which lends itself well to caricatures. While soft enough to carve fairly easily, “It’s hard enough to hold detail,” Floyd said. “You can do a lot of things with it you can’t do with other wood.” At times, he has also used butternut – usually when he does some of his occasional realistic carving, creating such things as depictions of mountain men. In those cases, Floyd said, he is not trying to create typical caricature features such as exaggerated ears.

He also carves commissions, which often involves people providing a photograph of a loved one whom they would like to see depicted in a carving. Floyd tries to tell a story about the person with the carving: for example, if the person enjoys fishing, he will incorporate that into the carving.

As for his caricature soldiers book, “I was inspired to do book because I’m a veteran, my father was a veteran, and I came from a time when veterans were not respected. We had things thrown at us. But sentiment in this country has changed. Now people are thanking veterans. My intention in doing the book was to applaud the other people that have served our country.”

In his own case, Floyd said, “The military was hard.” Woodcarving “helped with symptoms of PTSD. For me, it’s very therapeutic. It’s probably somewhat of an addiction, but it’s a good addiction.”

When he’s home in Michigan, Floyd said, he rises at 5:30 a.m., puts the coffee on, and carves until about 9 a.m. “I tell my students they should carve at least a half hour a day. If they do it, they’ll be amazed at how much they improve.” Floyd himself estimates he typically carves about eight hours a day – made easier by the fact that his spouse is also a woodcarver.

She doesn’t travel with him to his woodcarving classes around the country, because “A lot of times, I’m only seeing the classroom and the hotel room,” Floyd said, although he notes that “I see a lot of the road and get to meet a lot of good people all across the land.”

Often, he is going back to places where he has been before, and meeting some of the same people, leading to a reunion feeling.

That is definitely the case for Floyd’s own events in Evart, Michigan. The second week of June, he hosts a Wood Carvers Roundup, which hosts 60-plus workshops with free instruction in woodcarving. Participants pay only for materials. “It’s a good way for people to get introduced to woodcarving without spending a lot of money,” Floyd said.

2017 was the 19th year for the roundup, which Floyd says was the first of its kind in the country. The following week, he hosts a more structured event, currently called Floyd Fest, where participants take longer classes from the same instructor. This year was the 22nd for Floyd Fest. “Some people have been coming all 19 years” for the roundup. “They start to feel like your relatives,” Floyd said.

Floyd does wish, though that newer and younger people would become involved in woodcarving. “You don’t need a whole lot of tools,” he said. “Almost every town across the country has a carving club close to it. Go watch what they’re doing; that will get you excited. 98 percent of people who do woodcarving carve as long as they can until they’re too old to do it anymore.”