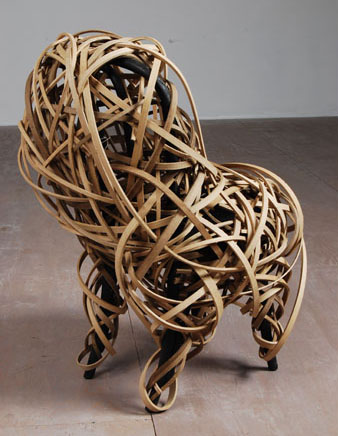

“As far as comfort level goes, chairs are the hardest thing to make,” insists Matthias Pliessnig. This may be true for him, but not everyone makes seating that looks like an undulating tide, frozen in time, whose surface is rendered in strips of bent wood. Matthias describes one particular piece of seating saying “it looks like two intersecting waves.

“It’s actually very comfortable and will hold a person lounging, or four or five people sitting. There’s a lounge section and a chair section, and all the geometries are taken from measurements of traditional comfortable seating.”

If that is the case, geometries are the sum total of what is traditional in his work. His pieces are both strong and comfortable, but look airy and fragile, often reminding one of a twisted basket, a bundle of reeds or an oddly twisted wooden grid. One piece reminded me of the new Chinese “bird’s nest” stadium where the opening ceremonies of the 2008 Olympics were held.

“I did no woodworking as a kid,” Matthias admitted, “but I was fascinated with taking things apart, though I was not too good at putting things back together. From a very early age, I started drawing. In high school, I got in a fight with my math and science teachers and decided to only take art classes and ultimately went to an art college. There I learned welding, and starting working in metal.

“By my third year there, I started to disagree with some of their design views. They were describing art as an object rather than a process, and felt design should stay on paper, whereas sculpture should not be designed. To me there is a harmony: the building component should be intrinsic to the design process. Building and design enable and enrich one another, creating a symbiotic relationship between the two. I could not design these things without knowing what the material is capable of, and would not know what the material is capable of without building with it.

“I transferred to [Rhode Island School of Design] RISD in 2000. The philosophy there was exactly what I was looking for in that they felt the understanding of materials was intrinsic to design. I joined the furniture design department and started learning woodworking. Wood is much different than metal, and at first I had a lot of trouble with it. There’s finishing, movement issues and many others; there was a lot to learn.

“I was looking for ways to build compound curves and felt restricted by the material. Eventually, I learned about coopering as a way to get around the limitations of wood. The result was Capsule, my first coopered piece, a box that holds an orthographic drawing of itself. Thus, the two things exist merely for one another. Pushing the plunger opens it, and releasing it allows it to close.

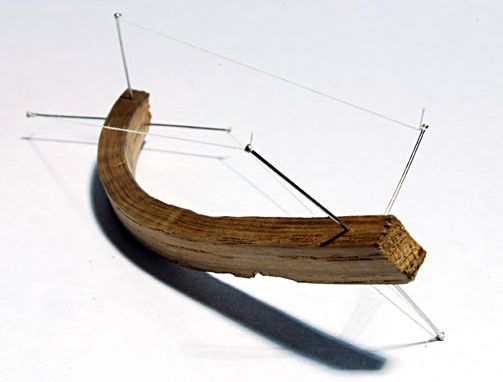

“After RISD, I joined a co-op shop and spent a couple of years doing furniture for architects. Between jobs, I built a few pieces, including about 14 coopered objects that I used as gifts to those who helped me. I also started building hundreds of tiny sculptures mostly of scrap. I was bored building things for the architects, so I started exploring structure and ideas with these pieces. Some have so much tension in them that they would not be practical in human scale. They are like little tiny balls of energy that I could explore without restriction and in a small space.

“For graduate school, I went to the University of Wisconsin-Madison and completed my MFA in May of this year. When I first got here, I was really floundering, and a professor, trying to get me to change my direction, got me to agree to stop coopering. However, before I quit I did a piece called Expanding Transit, made of 28 bent laminations, just to see if I could do it. The wall thickness is only a quarter of an inch, and the whole thing is very light. That was followed by Pierce and Void, two pieces that took that technique a bit further. That got coopering out of my system.

“To change directions, I decided to build an ultra-light boat, and during that process learned how to steam bend wood. That led to steam bending strips of wood to make furniture. The first piece I made after that was A Deviated Path, a large openwork bench. It was large enough that I did not need to steam bend the wood, so I decided to work with tighter curves.

“Along the way, I learned about making the right wood choices for steam bending, and started working with air dried oak at about 15 percent. At first, I used forms, but then switched to bending in air, and started using more open forms that look a bit like a draped carpet. To visualize the forms before I built them, I was using three-dimensional computer modeling. Dilapidated Flow was one of the first that let me see I could do things with more movement with depressions and swooping areas.

“Thonet Chair and Migration were moves back toward pure sculpture, and formed a way for me to forgo logic and simply play with steamed wood. Besides, I needed to build a body of work for a show, and decided to just build straight sculpture. Migration is large enough for a child to climb into. The initial idea was to build a whole fleet of those in different sizes, replete with oar holes so they could float and be propelled on a lake. My final piece, Providence, is a large-scale, structurally stable seating piece with a lot of fluid movement that incorporates both a seat and a lounge couch area, and could seat four or five comfortably.”

Why this drive to bend wood into such unlikely shapes? “Wood has a lot of natural plastic resins in it,” Matthias explained, “so it is capable of far more than what has been done with it in the past few hundred years. People are making very sexy and attractive forms with plastics, but I feel you can do anything with wood that you can do with plastic and carbon fiber. When you do, you end up with something much warmer and more alive, and made of a material that is more ecologically responsible and sustainable.”