When Brian Fireman went back to school for a master’s degree in architecture and worked a summer job for a construction company, “it was the seed for woodworking,” he said. “I loved all aspects of it, from layout to joinery to assembly on-site.”

On a break one day, “I was flipping through a tool catalog and ran across a small picture of George Nakashima’s book and Sam Maloof’s book.” Brian checked out Nakashima’s The Soul of a Tree and Sam Maloof, Woodworker, from the library around the same time he got into thewoodshop at Virginia Tech for the first time. Still, despite his interest in joinery, “I never in a million years imagined myself building furniture professionally. I thought it would be a hobby.”

That is, until he worked in an office as an architect for a couple of years. The former kayaking videographer — he had recorded commercial rafting trips by “playing leapfrog with my camera” against the customers’ crafts — said he “wasn’t very happy sitting in front of a computer.”

The first piece of furniture Brian designed and built, in school, was his Heron Table. Early on, he built most pieces, like his Sanctuary Table, for family and friends.

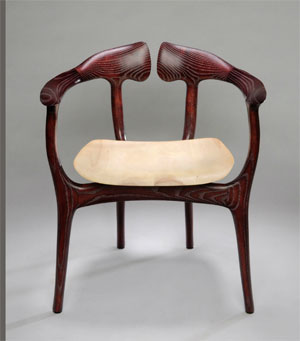

Then, the first design he did that was not directly related to a commission — “outside the boundaries of ‘it has to be this tall, this wide and made from these woods’ — was his Swallowtail Chair. “I’ve always been attracted to the design sensibilities of mid-century Danish furniture, with its joinery as well as its form and structure,” said Brian, and the Swallowtail Chair is an example of that influence.

It’s a lowback armchair and, Brian said, while “I loved how the arms and back connected, I wanted to do my take on that. I always wanted to split the spline on the chair but keep the support.” Brian has done several versions of the Swallowtail Chair; in most of them, the frame and the seat are made from contrasting woods, so they appear visually as two elements, while in one version, he ebonized the chair to a black color, so that the eye reads it as more of a uniformed form — “The seat becomes more of a focal point instead of the frame. The chair has different possibilities depending on what species ofwood I use and if any stain is involved.”

In general, the woods Brian uses are walnut, cherry and maple — living in North Carolina, he said, “I call these ‘woods from my backyard'” — with his preferences in exotics being cocobolo and wenge. Brian enjoys contrasting different woods within a single design but still, “I use walnut and cherry 80 percent” of the time, he said, largely because they hold lines and shapes well. “They’re easier than oak or maple, which are more splintery and prone to tearout.”

Brian’s working process involves milling stock to width, cutting the joinery on milled stock, band sawing it to shape, then starting his sculpting process using a variety of different grinders, working down to rasps, “and then it takes a lot of sanding.” In pieces like his glass-topped Wisteria Table or Malabar Table, he said, “you’re able to really see the sculptural work yourself.”

“I’m always interested in more flowing lines than straight lines,” Brian said. He’s also interested in shaping and following the natural characteristics of the wood itself, including grain direction and hard vs. soft lines. “I’m inspired by how limbs grow from trees, how things branch off and grow from each other.” Interested in outdoor activities from a young age, and with an undergraduate degree in geology, Brian said he also sees influences in his furniture work from “living outside, on rivers, kayaking and backpacking, geology: the landscape itself has been carved, shaped and sculpted over time, with the grain revealed.”

He also cites as influences, in addition to George Nakashima and Sam Maloof, Danish designer Finn Juhl, Italian architect and designer Carlo Mollino, American wood sculptor Wharton Esherick, and his “all-time favorite architect” Antonio Gaudi. Brian himself is close to becoming a licensed architect, having taken what he calls “the turtle path” to get there. “The idea is to combine [architecture and woodworking],” he said, taking things people want and “making it real.”