Chuck Zeman’s early interest in woodworking and hand craftsmanship lay dormant for a few years, but has been reawakened recently as he found himself collecting hand tools at garage sales.

As a child in central Wisconsin, Chuck said, he was making spears and stick bows with a pocketknife from an early age, taking advantage of the branches dropped by willow and box elder trees in his neighborhood. Then, at about age 10 or 11, he discovered Roy Underhill’s show “The Woodwright’s Shop” on public television. “I figured out years later,” Chuck said, “that what really fascinated me about it was his having the knowledge of how the grain worked, the knowledge of the wood first, to know that ‘if I do it this way, it won’t be as strong as if I do it that way.’”

Ironically, Chuck’s woodshop classes, in what he described as “pretty well-supplied workshops” contributed to his drifting away from woodworking for a few years. “It planted a seed in me that you had to have all that equipment to do things. I kind of forgot about hand joinery,” he said.

Still, Chuck maintained an appreciation for handmade items. He comes from a long line of craftsmen – his father was a shoemaker, and Chuck said he began sewing leather, a skill he maintains, at an early age. “Even though we’d go to buy furniture, I’d always look at how it was made. I didn’t want something just tacked together with screws.”

His appreciation extends to the tools themselves: “I was raised to have respect for tools. I kind of hate to see tools hanging on a wall in a restaurant. A tool was made to have a specific purpose.”

It was that viewpoint that led him, within the past few years, to begin purchasing hand tools at garage sales and estate sales. “I know how to use it, and it’s a dollar, so why not buy it?” was the philosophy.

Eventually, Chuck said, “I sat down and realized I have a whole shop full of hand tools and I could build anything I want.”

At first, he made a wooden mallet – “because you can’t do much with chisels without a mallet” – and a bench from cedar logs. “Then I realized I needed a cabinet to put these tools in.”

Taking inspiration from Dutch tool chests, Chuck had a design in mind, and then, “As I was driving to work one day, I saw in somebody’s garbage a pedestal from a waterbed.” His first instinct was that it was probably particleboard, but further investigation revealed 14” wide, 1” thick yellow pine. “There was all the lumber I needed for my tool chest,” Chuck said.

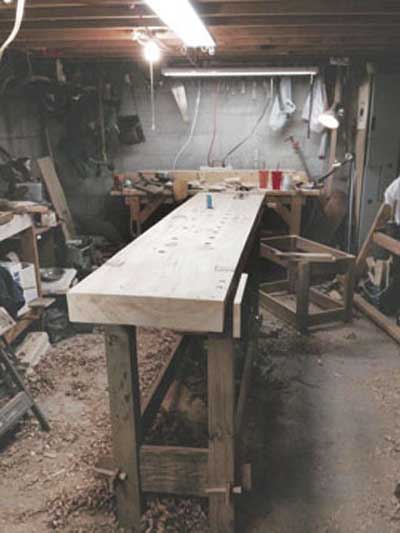

He also built himself a workbench; at 6’4”, “I needed a bench that fit me,” he said. “A regular bench is too low; I’d end up with lower back pain.” So, he started with a 6-1/2-foot x 4-inch slab of pine, hand planed it level, then cut it square. The horizontal stretchers are placed at a distance below the benchtop that is equivalent to Chuck’s measurement of his leg from knee to top of foot. “When I put my foot up on the stretcher, my knee is against the bottom of my benchtop. It’s my bench, built to fit me.”

A part of him, Chuck said, likes “finding” things. “I try not to buy cut lumber from a lumberyard. I like the idea of working with what you have instead of going out to buy specific wood for a pattern.”

Chuck also likes to build the old-fashioned way: without power tools. “If I do something small, I prefer to split the wood out a log, not cutting the fibers with a saw. It stays a lot stronger that way. If I cut materials, I’ll mark it with a marking gauge and cut it out with a chisel. I lean pretty heavily on chisels because of my whittling background. They’re familiar and comfortable to me,” Chuck said.

In fact, if he’s beveling the edge of a piece, he’s more likely to make the cut with a chisel rather than a plane; and if he’s making something like a split chair, he’ll put it in a shaving horse – which he built – and take the bulk off with a drawknife, then go to a plane.

“I rarely ever measure,” Chuck said. “If you’re working with pieces out of a log, it becomes much more beneficial to learn how to fit this piece together rather than rely on a set of measurements. You fit the second piece to the first, then the third to the second … I find it actually works a lot better that way than if you need a dado at ‘this distance’ and then one of the boards has a twist in it or you have to avoid a knot.

“It’s less like construction and more like creation that way.”

Still, Chuck points out, “I don’t want to give the impression I’m a master craftsman,” nor does he want to make objects for ornamentation. His preference with woodworking is to make useful items functional in daily life.

Chuck considers himself to typify “sloyd,” a system of handcraft in which one person makes an object, from beginning to end. “Before industrialization, one guy made everything: he cut the tree, he split the wood … whether it was carving a spoon or making a wooden toy for his kid,” Chuck said. “It’s all about the process to me. I want it to be my personal experience of making something and learning as I go.”

That’s a foreign concept to some, he says. “I’ve been whittling spoons on my lunch break at work, and people look at me like I’m from another planet.”

As he collects tools, he’s also gained more knowledge in that arena. “I’ve become kind of an antique tools historian; I’ve learned the history and progression of tools,” he said. “It’s kind of become a secondary hobby. I’ll go up to pay at a garage sale and they’ll say, ‘Do you know what it is?’ The loss of knowledge is kind of disheartening.”

And, in addition to collecting tools and making things with them, Chuck has also found it necessary to find ways to restore old tools. “I spent hours with steel wool before I learned about citric acid. With citric acid, you let it soak for a couple of hours, then the rust comes off with a towel. You don’t even have to work at it.”

All of these abilities give him a “tremendous feeling of self-reliance,” Chuck said. “You don’t have to rely on an electric motor. If a handle breaks, I can make a new one. It brings a tremendous amount of satisfaction to me.”

Chuck’s currently working on a panel chest for his daughter, inspired by 17th century versions; would like to make a wooden lathe, powered by a foot treadle; and, last summer, managed to buy an entire woodshed of mill-cut, live-edge, old-growth oak and ash. He estimates he’s got about 400 board feet. “I plan on making tabletops with it and anything else my imagination comes up with.

“I have one of those minds that can look at something and reverse engineer and figure out how I’m going to do it, or take examples from several different pieces, and put ‘em together, and make something.”