A few years back, Mike Dixon was visiting a lumberyard in Pennsylvania that had a hotel in the front of it. The owner explained that the sawmill business is always up and down, and he’d close it down when business got too slow, but the hotel was his bread and butter.

“He didn’t put all his eggs in one basket,” Mike recalled.”He was smart, and I’ll never forget that.”

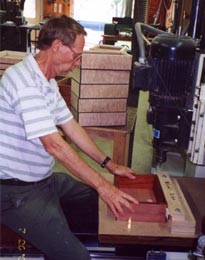

It’s a lesson Mike has put into practice in his own woodworking businesses. Today he has three distinct product lines for three different markets. Using exotic and beautiful hardwoods he makes inlaid tape measures for the craft stores and galleries, humidors for tobacco and cigar shops, and finished bodies, necks, and fingerboards for a guitar manufacturer.

Originally from Indiana, Mike and his wife spent a few years in Peru working for the Peace Corp in the late 1960s. When they got back, Mike attended graduate school at the International Business School in Phoenix, Arizona, writing his thesis on the hardwood industry in Brazil. He soon landed a job managing a sawmill in Nicaragua for an American company.

“They wanted the tropical walnut that grows down there, Mike recalled, “but it turned out it was too soft and punky and wasn’t worth anything. When our son was born, we came back and I found a job in Baltimore with a hardwood lumber company.”

As he learned more about the hardwood industry, he also discovered some of the frustrations of dealing with a commodity product. When the housing industry was up, he could sell all the lumber he had & but the sawmills wanted to sell it themselves. And when the economy was down, the sawmills wanted him to sell their lumber, but nobody wanted to buy it.

That’s when he had his epiphany after talking to the sawmill/hotel owner in Pennsylvania. In 1971, he started a craft business on the side & still working with the lumber company. Having no background in woodworking, he hooked up with a friend who had machinery and started making small craft items. He learned production through trial and error.

“We moved from Baltimore to Brownsville, Maryland, in 1973. I got into the Harper’s Ferry Art Show, which is in my own backyard,” Mike recalled, “and there was a company there with all kinds of wood products and kitchen items made of poplar, oak, walnut and cherry & domestic stuff. And through the lumber company I had access to all these imported, colorful hardwoods. So I jazzed up my line with imported woods and a more contemporary, less folksy look. I sold stuff like crazy at art fairs, but there weren’t that many back then, and it was pretty lean pickings for the first few years.”

Working as a lumber broker got Mike through those early days, but by the late 1970s and early 1980s he phased out the lumber side and was able to do 20 to 30 retail shows a year& even had a couple of people working for him. As the number of craft shows grew, he attended scores each year, selling his lines of kitchenware and desk accessories.

“Then as one line peaked another would wane,” Mike recalled, “so I added jewelry boxes.”

In the mid 1990s he was doing a show in New York City, and several customers mentioned that his jewelry boxes looked like humidors and he should try making them. It was in the midst of the cigar craze and Mike visited an upscale tobacconist on Lexington Avenue. He expected it to be like a newsstand where they sold cigars, but he found everybody in a suit and mahogany display cases. The humidors for sale were from Switzerland & the cheapest one was $500.

“I was totally impressed that they could get so much money for them! When I got back to Maryland, I looked up a tobacco shop in Washington D.C. and met with the owner and told him what I was interested in doing. He told me about humidors and what to avoid. One of the most important things I learned was the difference between jewelry boxes and humidors. They are built completely different.”

With a moisture level of 70% inside, the humidor’s core structure has to be MDF or plywood. A solid wood lid would fight with solid wood sides and soon warp as it expanded and contracted. Mike applies a veneer or 1/16″ sawn veneer to the top and sides. The other difference is the seal.

“When you close a humidor it goes ‘poof’ like a door on a new car.” Mike explained, “I can’t tell you my trade secret, but it’s critical to making a good humidor, and some woodworkers miss that. If you make it too tight the lid sticks, and if you make it too loose it slams shut like an Asian import.”

The cigar craze ended as fast as it began. To take up the slack, Mike started making parts for a guitar manufacturer. There are only a few kinds of wood that can be used on most guitars, but the company Mike works with makes resophonic guitars which uses a special aluminum resonator for the sound. That meant Mike could use any exotic wood he wanted.

“It’s still a backyard business,” Mike explained, “but more than a craft shop. Right now I have three or four employees, and that’s about all I want. Everything I make is a high skill product that requires good people and good machinery. Quality is most important. So now I’m staying at home and not doing shows so I can pay attention to quality.”

To see more of Mike’s work visit his humidors web site.