Ramon Gibbs traces some of the inspiration for his start in his woodworking to watching houses being developed in his small Ohio hometown community as a child. Using nails and such the workers left behind, plus some items scrounged from a neighborhood junkyard, he built a two-story treehouse. Ramon admits, however, that “that was a lot of ice cream seasons ago.”

He also found a basis of inspiration for craft from his mother, grandmother and great-grandmother, all crafters – his mother is a retired teacher of ceramics – who “used a little bit of everything: dirt, and wood, and clay.”

Ramon himself, in addition to taking a woodshop class in junior high, also studied upholstery, and then pursued that study in vocational school, eventually beginning his career in the retail upholstery business. When he studied upholstery, however, particularly with “the older guys I learned from,” Ramon said, “you actually had to learn about wood refinishing, wood repair: it was a part of woodworking.”

He used all of those skills as he did furniture and upholstery repairs for the dining rooms of such well-known restaurant chains as Bob Evans®, Steak ‘n Shake, Perkins® and Arby’s®. At the same time, Ramon was also providing those services to nursing homes, where many residents brought their antique furniture. “It was an ungodly amount of restoration time,” he said. “Things were broken, and I’d have to rebuild them.”

Eventually, Ramon moved from rebuilding others’ work to, with the encouragement of his wife, designing and building his own pieces of furniture. “My wife was really tickled, and it’s a lot of fun,” he explained. Following his first commission of a piece for the county sheriff that came about as a result of his displaying his work at a neighborhood festival, Ramon estimates he has made hundreds of pieces.

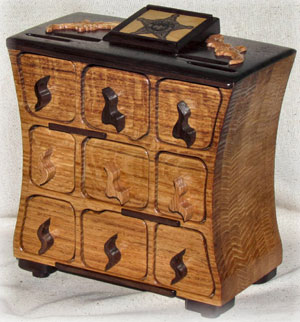

Although some are limited editions, most cannot be duplicated. “I don’t use patterns, and I rarely use rulers. No templates: straight from the idea to the wood,” Ramon said. He also indicated that he makes two types of jewelry boxes: one type he refers to as a “panel box,” done with flat panels in the style of cabinetry, as well as band-sawn jewelry boxes.

“Doing the band saw boxes can be a little more abstract,” Ramon said. “The one I called ‘Charmed,’ I wanted to give more of an Art Deco style, but then something like ‘Majestic Endeavor,’ I just allowed my creativity to follow that. Sometimes, the machine and the wood wants to do what it wants to do.”

Ramon says he does push his band saw “beyond the limits – but I know how far to push it.” For example, he frequently makes cuts at a very tight radius, using a 1/8” to 1/16” blade. “The manufacturer suggests that, with a blade that thin, you only go up to 2”” in depth of wood. Ramon, however, cuts up to 12” of wood. “I reduce speed so when I get to a concave or convex curve, or a radius, the bottom of the cut is not located on the top of the cut, and I feed it extremely slow – particularly when going through something like an Osage orange.” Ramon uses band saw blades with at least 18 to 22 teeth per inch to get his desired results; despite his adjustments in pressure and speed, he admits, “I go through a lot of blades.”

Some of his sanding techniques are different than generally recommended, as well, Ramon says. “It’s not always necessary to go through the full gamut of five to 10 different grades of sandpaper, for example. If I were trying to restore a piece, I would not take that to 1,500-grit. In many applications, you want the piece to look aged, so I won’t take it to a mirror finish.

“Any woodworking job is 10 to 15 percent cutting and 75 to 80 percent sanding, and who wants to sand? I’ve got old knuckles, and they’re not getting any brawnier. If you end up putting too much backbone into something, it’s overkill. And ask yourself this question: do they really want it to shine like new money?”

As for wood, Ramon says he works with of walnut and maple because they’re widely available in his area of Ohio, “but I would not apply those to an area where they were not applicable. I love the idea of designing, and I typically try to apply a design concept for what that wood is.”

For example, in his piece “Gatekeeper” – part of an exhibit of writing stations or miniature desks, and meant to symbolize the “gatekeeper” encountered whenever you call to ask someone a question – Ramon chose Osage orange for the pencil point legs because of the wood’s hardness. “It will withstand the test of time.”

In his “Piano” piece, created to symbolize what his wife felt for the recently deceased aunt who had cared for her as a girl, “I wanted to give as much shine as possible, so I chose a rich, deep, dark walnut. I guess there the wood speaks for itself.”

Those pieces Ramon cites as among those that are most meaningful to him, along with a U.S. commemorative wall plaque he did in the weeks after the 9-1-1 attacks. “My father was a military man, and that’s where my heart was during that time. I felt like I needed to give, and that was one way of giving.” The original limited edition pieces went to a select group of politicians, including then-President George W. Bush, and last year, the 911 Memorial Art Museum contacted him about including the piece in their displays.

Just as he used that piece to express his feelings in 2001, Ramon indicated that he finds it hard to answer questioners wondering things like where he gets his ideas. “You can’t teach creativity; you have to already have it inside,” he said. “From the standpoint of art, a lot of woodworkers don’t pick up on that it’s already there: we tend to overlook our own gift and not look within.”